When my father's grandmother first met my mother, she said: “Well, she’s not as pretty as the last one, but at least she’s not Catholic.”

My mother’s family, meanwhile, was aghast that their daughter was dating a Methodist. They were, and had been since well before they immigrated from the Low Countries to what became North Carolina, Baptists. Methodists were another tribe; rumor had it that some had been known to take a drink. And, of course, part of my father’s family came from New Jersey, which was far away and known to be populated not just by Methodists but also by Catholics. There is no record of my mother’s parents’ having been grateful that at least this son-in-law was not Catholic: I expect that it didn’t occur to them to imagine that a Catholic could ever enter their family.

These conversations all happened in the early 1960s, when almost three-quarters of Americans belonged to a church, mosque, or synagogue. That figure has dropped steadily in the last quarter century. It may be difficult to think yourself back into a mindset where church membership was a central part of our social identity. Church was where you were married and buried. It was also where you spent at least part of the day Sunday, and likely another day during the week. It was where your kids went to Sunday School and joined the youth group, where you knew people you had grown up with, people you trusted to bring you a casserole when times were tough. Church was part of how we constructed our social worlds and personal identities. Marrying someone from a different faith was a big deal.

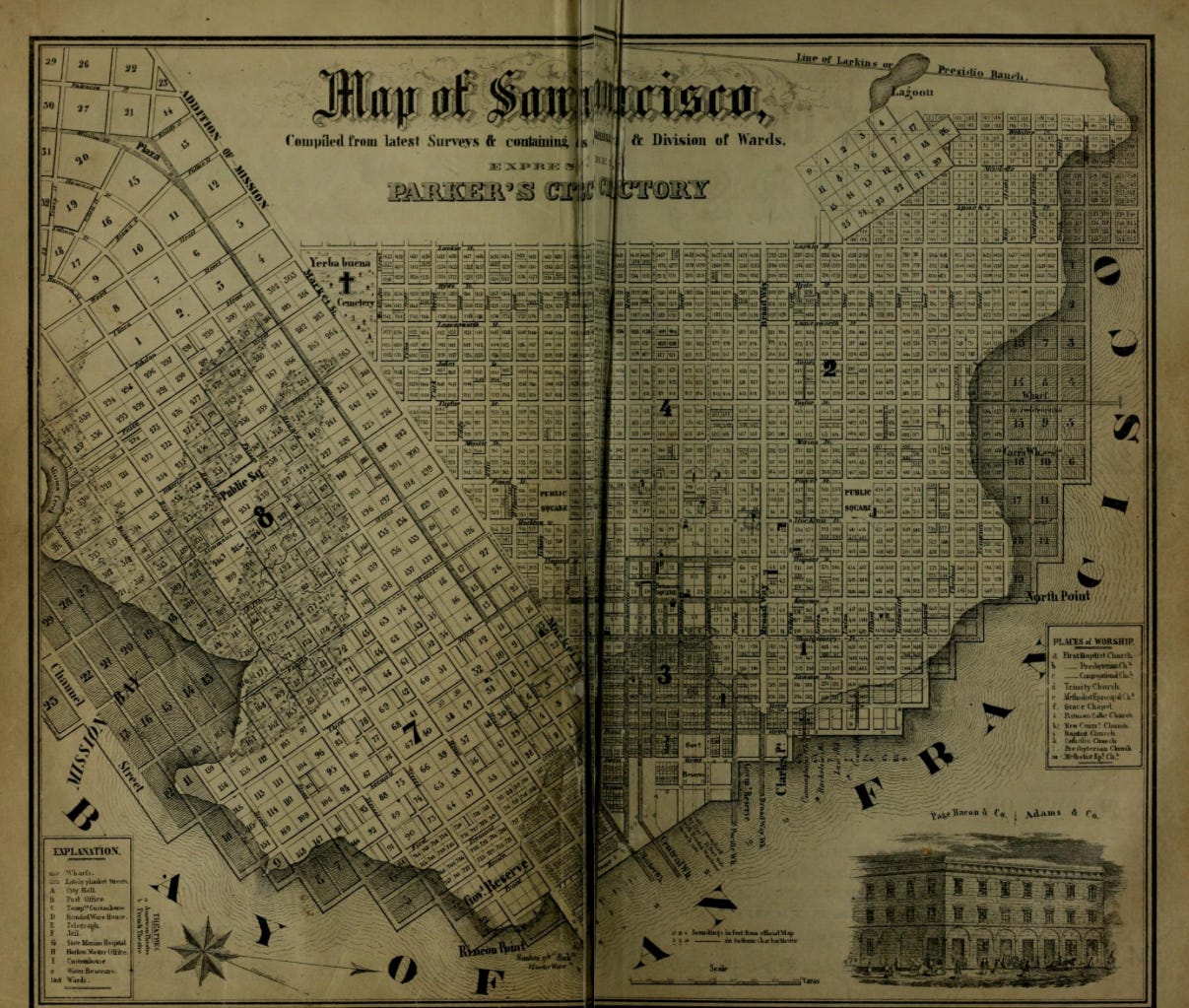

The Klumpke sisters were the product of a seventeen year marriage between a Protestant and a Catholic. Their parents married in 1855 and divorced in 1872. I’m curious about the way this shaped Anna and her sisters’ early lives. In her 1940 memoir, Anna would explain her parents’ divorce as the result of tensions between her strong-willed mother and a Catholic aunt who interested herself too closely in the children's religious education. The elderly artist still saw interfaith marriage as a central element of her family’s story.

In 1842 Heinrich August Tolle and his wife Elisabeth arrived in New York from Göttingen, Germany, with their five daughters. The people of Göttingen had been Lutheran since as long as Lutheranism had existed, since the early 1500s. For more than two hundred years, there was not a Catholic church in the city. The Klumple girls could have spent their whole lives in Göttingen without knowing anyone of the Catholic faith.

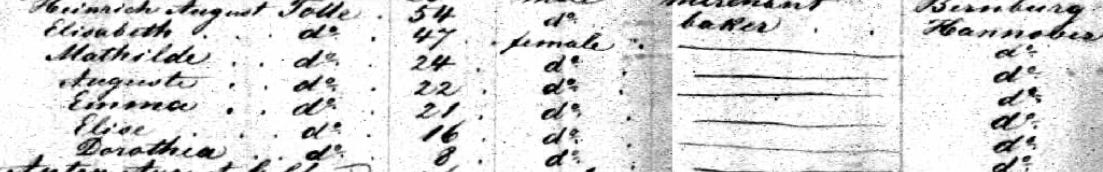

The Tolles settled in New York. Augusta, the second daughter, married another German immigrant, Adolph Plate, and by June of 1852 the young couple had moved with their young son to San Francisco. Adolph opened a gunsmith shop at 55 Liedesdorff Street, a few blocks from the city’s docks, and the family made a home. The next year Augusta’s youngest sister, Dorothea, joined them. On October 28, 1855, she married another German immigrant to San Francisco, a bootmaker named John Gerhard Klumpke.

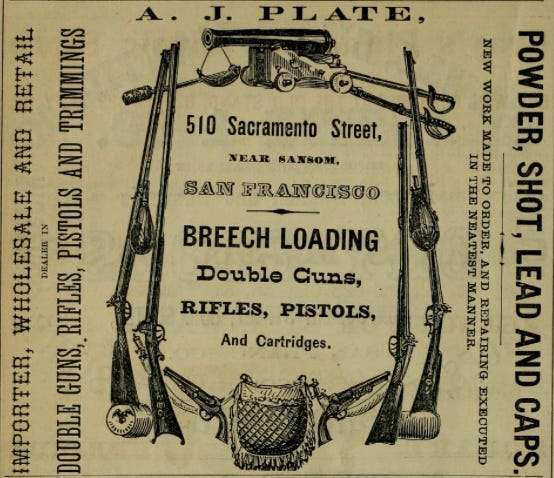

Klumpke immigrated from the village of Suttrup, about 175 miles northeast of Göttingen, in 1843. He traveled with a friend who would become his business partner in San Francisco, John Pfeiffer. The young men first came ashore in New Orleans. The record of what they did there is fuzzy: some sources say that Klumpke went to medical school, but if he did, he never practiced. Klumpke and Pfeiffer landed in Santa Barbara on August 20, 1850, and worked their way north to San Francisco. They opened Klumpke & Co., makers of boots and shoes, at 154 Montgomery. All those miners heading for the hills needed sturdy boots: the directory listed 33 bootmakers in the city of 13,785.

John and Dorothea were part of the German immigrant community in San Francisco. Drawn by the promise of the gold rush, German immigrants accounted for about 11% of the city’s population in 1852: about 1600 people out of the population of 13,785. In the mid-1850s there were, at times, as many as a dozen German language newspapers. There was a German Club, located in the same block as Klumpke & Co. Dorothea’s brother in law’s gunsmith shop was only less than two blocks away. There was a German sharpshooters club and assorted saloons, restaurants, and amusement parks that catered to a German-speaking clientele. There were plenty of places for their courtship to unfold.

One thing that John and Dorothea did not share: their religion. John was Catholic.

Both the Catholic and Protestant traditions abjured interfaith marriages. Writing in 1879, Roman Catholic priest and historian A. A. Lambing laid out the Church’s opposition to marriage between Catholics and non-Catholics: “Mixed marriages are contrary to the natural, the divine, and the ecclesiastical law.” Lambing noted the risk of children being “either without religion” or brought up in “the tenets of a sect condemned by the Church as heretical.” Were a Catholic to become accidentally engaged to “a Protestant or an infidel,” it would be a “sin as well as an imprudence” not to break off the engagement. Breaking the engagement would be “a positive duty, just as much as it would be a duty, for example, to break a promise of attending a Protestant meeting on Sunday instead of going to Mass.”

A few years later, the editors of The Lutheran Witness published a detailed article, “Matrimony--Mixed Marriages.” These they defined as “between Christians and pagans, between Orthodox and heretics, between Protestants and Catholics, between Lutherans and Reformed.” The news was not good. “Experience has shown,” they wrote, “that mixed marriages very often prove to be sources of unhappiness on account of the religious discord that follows from strife of conscience in the same household.” One cause of strife: the bringing up of children in the correct faith. “Romanists” were known to insist on their children being brought up Catholic, despite the desires of their Lutheran spouses--”and the thought that his or her offspring are made papists will continue to be a heavy burden.”

Marry outside your faith, and you could find yourself living with someone whose holiday traditions were different, who saw the world through a different lens. You could find yourself with someone whose family stories had to be edited or explained in the telling. Your children could be spirited off into another faith, another culture, another view of the world. Religious life was a significant part of cultural identity, and J.G. Klumpke and Dorothea Tolle came from traditions that were not only different but that actively distrusted each other.

The Saturday, June 2, 1855, edition of the Daily Alta California newspaper listed 26 “Places of Worship in San Francisco.” Two were Catholic; the rest were garden variety Protestant, from Episcopalian to Unitarian to Church of God. While there were no Lutheran churches, there were two Baptist churches and one Presbyterian church that offered services in German.

Dorothea Tolle and John Klumpke chose to be married not in one of the Catholic churches, and not in any of the churches that provided services in their native language. They were married, instead, by the pastor of Calvary Presbyterian Church, on Bush Street, “opposite [the] Musical Hall.” Dorothea did not convert to Catholicism. Had there been any of John Klumpke’s family to protest, the story might be different: the wedding might not have taken place, or the cultural pressures would have prevailed on the young woman to capitulate. If Anna’s sister Augusta and her husband frowned on the union, there is no record. Neither did John give up his Catholicism. When he married his second wife twenty years later, he chose a Catholic woman who was active in the city’s German Catholic parish.

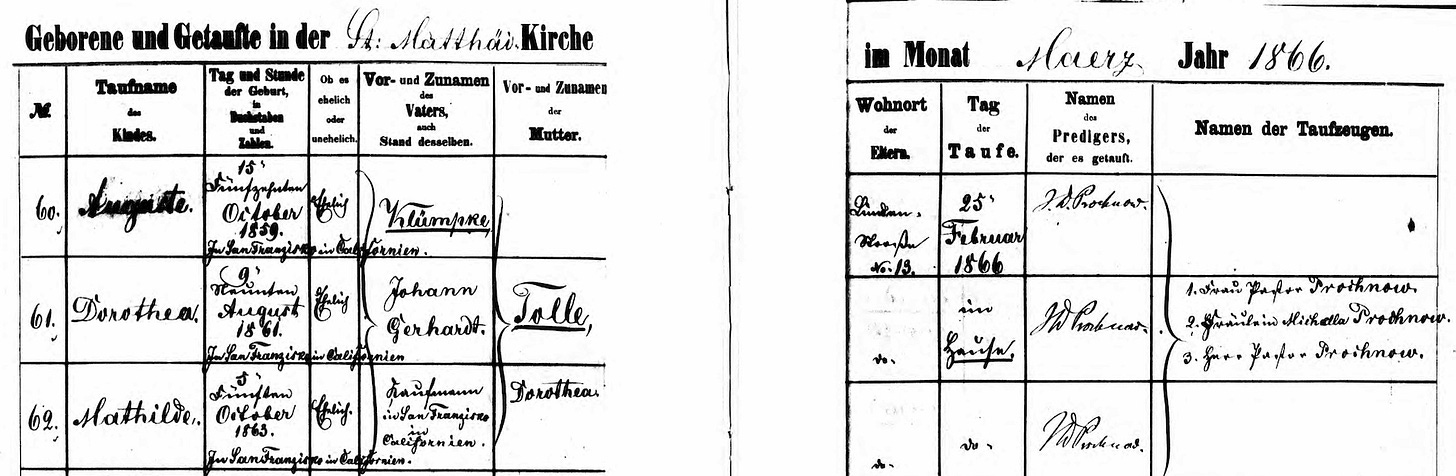

In October 1855, though, the young couple decided to go against both their religious traditions and marry someone who their faiths would identify as a heretic. Their first child, Anna, arrived the following August. We do not know into what, if any, church congregation she was welcomed. Dorothea would take her children back to Germany a decade later for a two-year stay. During that stay, she had three of her daughters—7-year-old Augusta, 5-year-old Dorothea, and 3-year-old Mathilda—baptized in the Lutheran church of St. Matthias in Berlin.

Not only did Dorothea Tolle not convert, she had her children baptized Lutheran. In another country.

Why is this worth drawing out, in a story about the Klumpke daughters’ international adventures?

I want to find out how Anna and her sisters grew up to become the women they were. I don’t have access to their letters and diaries, if they exist. I do have access to genealogical records and contemporary newspapers. Out of those sources I can pull threads to weave this first version of their story. I don’t have Dorothea’s journal to tell me what she thought about this brash, loud, dirty, foggy place she had followed her sister to. I don’t know much about John’s early life, or what he hoped for when he arrived in San Francisco. Was he searching for gold, or did he see himself as a merchant outfitter to the gold miners? I don’t have photographs of the couple, or stories about how they met. I only have what I can piece together, toggling between census records, ship manifests, and the spotty records of the earliest newspapers in California. To that I can add secondary source material about marriage and faith and culture and immigrants in mid-1800s San Francisco: numbers and figures and other peoples’ dissertations.

Census data and city directories can only take us so far. Where it stops, imagination and empathy start. What was the world that Dorothea Tolle and John Klumpke walked out into each morning in San Francisco? How did they meet? Was he a friend of her brother-in-law's? Someone she knew because he, like her, was part of the German community in San Francisco? Did the two fall in love—or did they size each other up and work with what they had? What did their married days look like? And what led to their divorce? Was it, as Anna recollected, the tension between their faith traditions?

I can’t know these things. I can imagine, though, 32-year-old Dorothea in rented rooms in Berlin, dressing her daughters in their best clothes, braiding their hair, polishing their boots, and bundling them into the church on a cold February Sunday. The pastor of St. Matthias, J.W. Prochnow, baptized them; his wife and daughters stood as their godparents. I hope they all went home afterwards for a festive lunch of something warm and sustaining. Dumplings, maybe. Strudel.

Dorothea and her children went back to California in 1867. Four years and two more children later, they left again, probably traveling by ship from San Francisco to Panama, across the isthmus by donkey, and then up the coast to New York. The marriage was over. On September 13, 1871, Dorothea stood on the deck of the steamship Westphalia with her five children—Anna, 15; Augusta, 13; Dorothea, 11; Mathilda, 9; John William, 5; and Julia, barely 12 months old—and watched New York and the continent recede. They traveled first class, which must have made the trip with small children a little easier. The Klumpkes’ divorce would be final in 1872. Dorothea never returned to San Francisco.